This New Offensive

(Ebro 1938)

This new offensive drugs our old despair,

Though, distant from the battle-line,

We miss that grave indifference to fear

That has so often now saved Spain.

Let fools and children dream that victory

Drifts lightly on the wings of chance,

And all that riveted and smooth-tooled army

Should melt before this proud advance.

Not this war’s weathercock, brave when things go well,

Afraid to think of a retreat,

By turns all singing and all sorrowful:

We’ve not to watch but win this fight.

Offensives must be paid for like defeats,

And cost as dear before they end.

Already the first counter-raids,

Take no positions but they kill our friends.

A miracle is not what we can hope for

To end this war we vainly hate.

We shan’t just read it in the evening paper

And have a drink or two to celebrate.

For two long years now when you sighed for peace

To slip from heaven as an angel drops,

You were confronted with your own sad face,

And once again time holds the mirror up.

It was not a few fields they sought to gain,

But months and maybe years of war.

Time’s on their side: by time we mean

The heirs of time they thought worth fighting for.

This narrow ridge of time their valour won,

Time for us to unite, time to discover

This new offensive is your life and mine,

One nation cannot save the world for ever.

Margot Heinemann 1938

Published in Poems for Spain 1939 [1]

1. Heinemann, M., This New Offensive (Ebro, 1938), in Poems for Spain, S. Spender and J. Lehman, Editors . 1939, The Hogarth Press: London. p. 24-25.

Purple, yellow and red, our banners catch the sunlight streaming through the medieval gateway. It looks like a movie about the middle-ages, not a 21st century visit to a 20th century war zone. We have reached the old town, the ghost town, of Belchite. This arched gatehouse was one of the only ways in apart from the water conduits. The outer walls of town are the windowless backs of the outermost houses. Inside there were handsome town houses, many churches, convents, monasteries and also a hospital and a social club where people could dance or watch movies. Now all are ruined. A broken jigsaw of the architecture the tourists photograph in Zaragoza or Huesca.

Purple, yellow and red, our banners catch the sunlight streaming through the medieval gateway. It looks like a movie about the middle-ages, not a 21st century visit to a 20th century war zone. We have reached the old town, the ghost town, of Belchite. This arched gatehouse was one of the only ways in apart from the water conduits. The outer walls of town are the windowless backs of the outermost houses. Inside there were handsome town houses, many churches, convents, monasteries and also a hospital and a social club where people could dance or watch movies. Now all are ruined. A broken jigsaw of the architecture the tourists photograph in Zaragoza or Huesca.

This place looks like Gaza, Bagdad, Banja Luka. It looks like a demolition site. It smells like one too, of dirty plaster, dry rot and brick dust. I do not understand why – after nearly 80 years you would expect the dust to have settled. Our guide, a young woman, explains. She warns us to be careful, not all the buildings are safe,-it would be dangerous to go off on adventures of our own. The damage we see now- the wrecked buildings and splintered wood, does not all date from the civil war. Franco decreed that Belchite should be evacuated and a new town built, by the forced labour of Republican prisoners, down the hill where our coach is parked, where we will have lunch. The empty buildings were to remain as a terrible example of what would happen to those who defied El Caudillo.Of course not everyone was welcome in Franco’s new town. Republican sympathisers left quickly to live elsewhere. And the former inhabitants, whatever their political affiliation, stripped the buildings, taking out anything they could use in their new homes.

In Franco’s time the site was preserved, after a fashion. When the Socialists were elected there was some money to maintain and repair the site. Now, the government gives nothing. The damage you see, says the guide is mostly from the weather. Some, not all. She shows us the church tower with an unexploded shell still lodged between the medieval bricks.

Belchite changed hands three times the guide tells us. The first time the Republic took the town they evacuated the civilians. Our guide’s grandmother used to tell her how she had to put on all the clothes she owned to carry them with her. The International Brigaders, including volunteers from the US and Ireland, were here when the Republic took the town for the second time. Republican troops besieged the town but were only eventually able to get in after they cut off the water supply, and eventually entered the town through a dry water-course. We look across the pale rubble and imagine how long a town would survive without water in this climate.

The town, the guide tells us had no particular strategic significance, but the Republic badly needed a victory after the failure to take Santander.

We stop I look round the faces, of the group especially those whose relatives had served here. Manus’s father, Nancy Wallach’s father, Nancy Philipps’ uncle. They look sober. None of us talks much. We have all read about the war, some have visited Belchite before, though not with this guide. She clearly has Republican sympathies but the stories she tells are of the horrors of war. House to house, hand to hand fighting. Killing or being killed.

There are weeds among the broken stonework, with little yellow flowers. I find myself humming under my breath, “Where have all the Flowers gone?” one of Pete Seeger’s songs though not, at least officially, a Song for Spain. I realise why our parents, why we, the individuals who make up this group, have devoted so much of our lives before 1936 and after 1945, to the Peace movement. This was a war that had to be fought but all modern wars, perhaps all wars, are horrible and destroy young lives.Hugh Sloan, Paddy Cochrane, Sam Levinger. As Christy Moore reminds us, “So many died I can but name a few.”

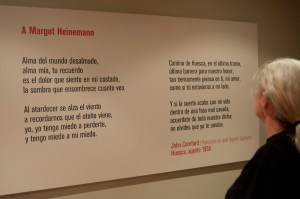

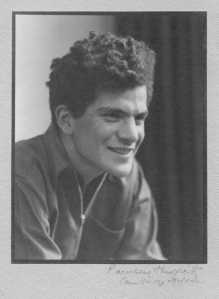

In 1933 Cambridge students, including John Cornford and Margot Heinemann, set up an Anti-War Exhibition with “pictures of men with their faces blown away, that kind of thing” They were both involved in the Cambridge Armistice Day riots in that year, when a peaceful demonstration offended militaristic right wing undergraduates into well organised physical violence. John was killed outside Lopera in December 1936. I remember my own father, who spent so much time in the fifties and sixties on the World Peace Council, time that he could otherwise have spent on science, or with Margot and me. Perhaps he might even have won that Nobel prize. If this is what even a just war is like we are right to fight for peace. “Even a just war is horrible, even a horrible war may be justified.”

The guide points out a cross on the village street. A seven year old girl went out after curfew on a quiet day, believing it was safe. The republican soldier had orders to shoot anyone who moved. Her father carved the cross in the place where she died.

There were too many dead fighters to dig graves for, so they took them to the old olive oil mill and buried them there. The memorial is caged and padlocked, Behind the grille you can read the contested history of this war in layers of broken stone. First the fascists put up a memorial. After Franco’s death the Republicans did not destroy it but put another stone in front, hiding it. Falange sympathisers came in the night and broke the Republican monument but did not remove it. There are some spray-painted graffiti. No, not all the damage here was done by the weather.

It is Sunday. As we walk back through the town to our lunch people are coming out from Mass, Manus comments on our republican T shirts and banners. Nobody could be a stronger supporter of the second republic than Manus but he asks if we are being unnecessarily disrespectful. I feel a little ashamed not to have considered that myself.

Later I read that the Fascists did not shoot prisoners on Sundays, just on every other day of the week. If that was their respect for religion, perhaps my scruples are a bit silly.

Lunch is good but slow. I enjoy the scrambled eggs with spinach but there is no doubt that the little pink bits that speckle the green are shrimps. The vegetarians can’t eat it and an alternative has to be prepared. Then there is just one loo, which also slows us down. We are late back to the coach and our meeting with Antonio Jardiel at Quinto.

We sit in the darkness of a cool public building watching film of the brigaders, like a family watching ancient home movies. “Is that your uncle?” “Oooh, look there he is, is that Bill Alexander?” Then we go out into the scorching plaza in front of the huge church to hear about the battle for Purburrel Hill and for Quinto itself. We stand in quiet groups, perhaps because it is hot, perhaps because this is a place where the International Brigades showed great heroism and also where their commander, General Walter, shot unarmed prisoners.

Antonio follows the coach in his car so that he can show us Purburell Hill itself. It does not look so high. We could climb up that prickly scrub-land ourselves in an hour or two. “In battledress, with all the kit?” someone asks. ”Strafed from above?” We try to imagine ourselves scrunching down into tiny depressions in the steep scree, behind little rocks, seeking out what cover we could from the sparse spiny vegetation. The Nationalist aircraft made a mistake, they believed the Republicans had already taken the hill and bombed their own forces but the Brigaders on the hill did not know that.

I am not sure if I want to hear about any more battles today. I am ready for a long cold drink and some good tapas, when we reach Caspe but everybody tells me Anna Marti is worth hearing. They are right.

Several people in our group are from the Clarion Cycling Club. At first I could not understand why one of them insisted on wearing an acid yellow jumper and cycling shorts, when there were no bikes to be seen. Lycra? In this heat? It seems that in 2008 they made an epic journey, cycling from Glasgow to Barcelona in memory of Geoffrey Jackson and Ted Ward who, in 1938 cycled from Glasgow to Barcelona to raise money for Aid for Spain. In 1938 they had to ride through France but the 2008 trip chose a different route and TV cameras followed them down Spain. Terry of the maillot jaune introduces Anna Marti, a young Catalan, who rode with them. She is here to tell us about her research onthe Great Retreats and the ordeal of the Lincoln-Washington Battallion. The lights go down. A Power-Point presentation. I am afraid I may fall asleep and know that people will notice if I do. The hija de Margot Heinemann can get away with less than plain Jane Bernal in this company. Nancy Wallach and Nancy Phillips had relatives there, I tell myself. You owe it to them to stay awake

I need not have worried. It is a brilliant presentation. Moving, well researched, beautifully illustrated. Every map, every photograph, is easy to read and is there for a reason. The Brigades were camped over a wide area of country, groups of two or three men each bivouacked in a chabola, a shack, made of dry-stone boulders roofed with pine branches. Hy Wallach was there, Alun Menai Williams & many others. Brigade Headquarters were in some farm buildings down in the valley. Many of the men were new recruits, it was their first action. The orders came to retreat to the Ebro. Men from each chabola tried to make their way there, without maps, travelling at night to avoid bombers. They did not realise the Condor legion had out flanked them so that they were more or less surrounded. Each tiny group desperately headed in what they hoped was the right direction, shedding kit and even clothing to lighten the load they had to carry. Very few made it. What Anna has done is literally to put this journey back on the map. She pulled together all the accounts of the surviving brigaders. Local historian Vincenc Julia went to the local people with a questionnaire. “Where did you see a living brigader?” “And a dead brigader?” The two accounts tallied. Then she went across the field and the hills using the oral history to find the chabolas, entering each onto a map. The work took years. This was not for an academic degree, nor is this her paid job. We used to play a game at academic meetings, I remember, based on Olympic skating or gymnastics. So many marks for style, so many for content. Few got straight tens in both. Of course I am partisan about the content and I am not a historian, or even a proper social scientist, but this looked to me like straight tens across the board.

Tomorrow we will be walking the hills with her, seeing what remains of the chabolas. I can hardly wait.

Further reading

Belchite

Franco’s repression/ Quinti

The Spanish Holocaust. Paul Preston, HarperPress 2012

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/mar/09/spanish-holocaust-paul-preston-review

International Brigades

Unlikely warriors. Richard Baxell, Aurum Press 2012

Anna Marti’s work

Describing events on 19th October 2014. Posted on 9th April 2015